The rise and fall of the Nigerian Economy

Nigeria’s Economic Rollercoaster through the eyes of citizen

By Samuel Ajayi

It was past 6 pm or 7 pm, I could not clearly remember, I was tightly strapped to the back of my mum, a heavy rain had just turned the only bridge out of the street into a dangerous spot. The banks were flooded, yet we needed to get home. She carefully tested each step to ensure we didn’t slip into a mass of water. A few years after Nigeria’s return to democracy, this particular bridge was rebuilt and the street was fully tarred. If there was a story that described how policies and development can make a valuable infrastructure available for the masses.

The honeymoon rise

I remember days like this because they tell a story about Nigeria’s economic rise through the eyes of a boy born in Ondo to a civil servant mum and a teacher Dad. Salaries were irregular and the standard of living was poor. This was the prevailing economic situation that I was born into. Often, the story of Nigeria is not written through the direct impact it has on regular people who feel that impact. The story of Nigeria’s economic rise in the early 2000s is often seen from a pure numbers perspective but many like me have stories to tell about our lives.

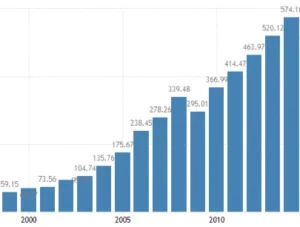

We watched as the Telecoms liberalization policy happened and phone lines that were only accessible to a select few became something accessible to the common man. Before we had access to phones, my cousins and I would construct wooden replicas of phones and mimic making calls on them. An interesting happened when my mum took delivery of her Samsung R225, we stopped making replicas and actively started using phones. The substance of our aspiration had become a common reality. Such is the impact of economic growth on the lives of people. To put this in perspective, NITEL, a state-owned monopoly, has dominated the telecoms industry, with approximately 700,000 lines nationwide since its creation in 1985. Following the sector’s liberalization in 2001, things moved quickly. There are now more than 185 million phone users in Nigeria by 2021, the anniversary of the sector’s deregulation.

The Average GDP growth per year between 2005 and 2013 averaged 6% per year after having hit a record high of 15% in the year 2002. These were the years of serious economic impact on the lives of the people. It was during this period of consistent growth that my family bought their first coloured television, acquired two cars, and bought the land that was eventually developed into a house. The optimism in the air was palpable too, it was not uncommon to have students brag about their ability to use the internet. Many of those students hadn’t seen a computer before only a few years before. Students would mail UK universities which would send students their Brochures, those became status symbols of savviness among students. This would eventually encourage them to pick up computer skills. Uncles and Aunties in foreign countries regularly inquired about Nigeria, some even started coming back. They moved back home to start businesses and start again, it seemed that the good days were here to stay.

Now that television had become very accessible, kids like me could catch up on new TV shows and cartoons. The Nigerian growth that had been driven by reforms in several key sectors, the oil boom, and, the return to democracy had lifted several people out of poverty and many were on the way to middle-class status. Nigeria’s economic growth profoundly affected me since we went from walking to owning a family house and two cars. Several other families even had it better and we all thought the rise was inevitable.

The famous decline

The story of Nigeria’s economic fall from grace is what I describe as the hubris of inevitability– there comes a time when things are going pretty well in a country relative to where it was before and genuine concerns are turned into a battering ram by a range of interests who argue that what was done was rather inevitable. The populace trusts them with political leadership and things often go from bad to worse or good to bad. Let me borrow a leaf from the famous English writer GK Chesterson, famous for the Maxim “Chesterson’s Fence”, which is simply paraphrased as this “Do not remove a fence until you know why it was put up in the first place.” in his comments on reform, he further stated.

“There exists in such a case a certain institution or law; let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, “I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.” To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: “If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.”

My amendment would be to say “Do not evict a political party from power based on their success being inevitable unless you can demonstrably show why what they are doing was inevitable” This may have done us some good as the winds of political change blew across the nation in 2014. I will not shy away from the fact that livelihoods are a direct result of political actions or inactions. I was a student with a keen interest in politics at that time, the debates were often heated and passionate but there existed a strain of the hubris of certainty in many who were advocating for the removal of the incumbent government.

This in itself may have been the first step towards Nigeria’s economic fall

Discontent is a good political organizing tool and often galvanizes people towards political action in remarkable ways but it often requires simplistic narratives and irrational fervour which can relegate good thinking to the back burner of political debate. This in itself gives rise to people with exciting but bad ideas coming on board, people who would readily violate my amendment to Chesterson’s law.

A new government came to power and a series of catastrophic decisions sent the Nigerian economy into a tailspin, followed by a series of recessions. A raft of bad ideas followed as Bryan Caplan rightfully noted in his famous article Idea Trap, it is in the times of great dissatisfaction that people are more likely to try out terrible ideas as he rightfully notes;

“A society can get stuck in an “idea trap,” where bad ideas lead to bad policy, bad policy leads to bad growth, and bad growth cements bad ideas.”

If there was a word that described Nigeria’s economic fall the actions that led to it and how each action from then has only seemed to make matters worse. Nigeria lost immense value and inflation started taking a toll, many people could no longer afford the necessities. The COVID-19 pandemic sowed a blow and the scenes of people besieging food warehouses went viral on social media. Walking through the streets, it was now a regular occurrence to encounter people begging for food. Even in the times of growth, this was not a regular occurrence.

It was clear that the years of growth were gone and as I settled into my adult life, it would be marred by intense economic hardship. Many colleagues that we went to school together struggled to find useful jobs as companies closed shop one after the other. The year 2023 was particularly marked by lots of departures.

When times are tough, people take to the exit with urgency–Many friends start whispering about relocation to other countries. I have now become accustomed to the loss of another kind, losing friends and long-term acquaintances to the distancing hand of japa as it’s commonly called creates a sense of loss that’s akin to death as some will never see me again till they are called to their creator. I have been urged many times by friends and family to head for the door, the consensus is that those who live here are those whose hope has been abandoned in a twist to Dante Alighieri’s famous words.

To close this article, Indeed many of my age who witnessed the economic rise have not experienced an economic boom in their adulthood.

The question arises, does it seem like the Nigerian economy will rise again? The optimistic answer will be yes. The newly elected government keeps touting a reform agenda but the cost of the reforms has not been easy on Nigerians. The reforms while needed are viewed with suspicion, the political elites have simply passed on the cost of reforms to the populace while they continue to feed fat.

There is unease in the air

The optimist still roars that it is not yet over, the alternative is pure anarchy. The hope is that the reforms restart visible economic growth quickly.

My name is Samuel Oluwafemi and this is Nigeria’s economic history as I’ve experienced it till now.