Across Kano State, vulnerable communities are facing a growing healthcare crisis: broken-down clinics, critical shortages of staff, and essential medical equipment that simply does not exist.

By Mariya Shuaibu Suleiman, May 2025

Despite Kano State’s repeated promises to improve primary healthcare—and billions of naira allocated on paper—rural families are left to fend for themselves. With abandoned facilities, no trained staff, and severe gaps in basic services, women, children, and people with disabilities bear the brunt of a failed system. As expectant mothers are wheeled in wheelbarrows in the dead of night in search of help, in this investigation, Mariya Shuaibu Suleiman exposes how systemic neglect, unfulfilled budgets, and crumbling PHCs are putting lives at risk across Kano’s rural communities.

In Bichi, Kano State, the first scream tore through the night around 1:00 a.m. in Kwamarawa village. Khadija Ismail, just 22 and nine months pregnant, was in labor. Her mother, frantic, grabbed a wrapper. Her husband, Ismail, bolted into the darkness in search of help. The village’s Primary Health Care was less than a ten-minute walk away, but it might as well have been on another planet.

There were no lights. No doctor. No nurse. No water. No delivery bed. Just one broken bed frame rusting in a dark room. The PHC closes by 2pm and does not open on weekends unless on official calls.

They carried her in a wheelbarrow to the roadside, hoping to find a motorcycle taxi. It was almost dawn by the time they reached a hospital in Kano city, many kilometers away and a more than 2 hours journey.

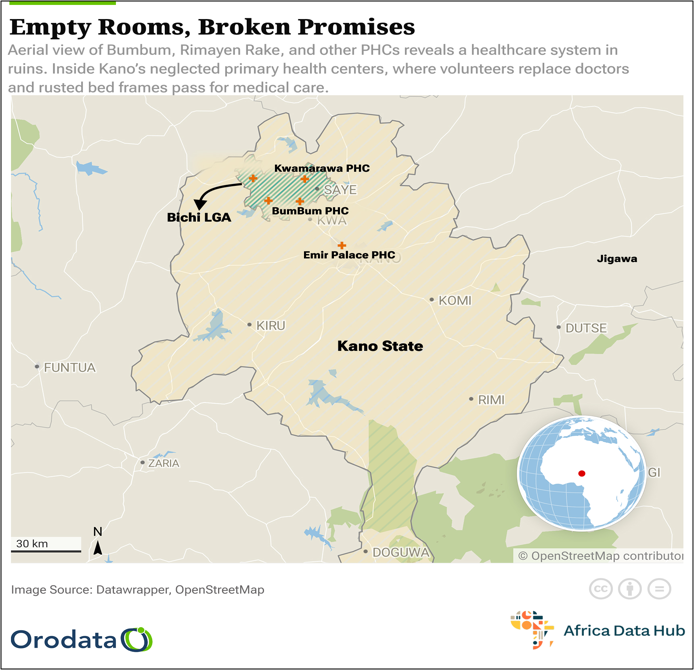

This was not a fluke. It is the reality across five Primary Health Clinics or Health Posts in Kano State: Rimayen Rake, Kwamarawa, Bum Bum, and Tsaure in Bichi LGA, and Emir Palace PHC in Kano Municipal. All of them share the same tragedy: abandoned buildings bearing the name of healthcare, but none of its life-saving function.

The Only PHC in the Village, But Useless in Emergencies

Inside their small hut,Ismail Musa, Khadija’s husband, recounted their experience with a quiet shake of the head.

“We ran there first because it is the only Clinic in this village,thinking someone would help us.

But it was like a ghost house. No water, no light at the Kwamarawa Clinic. My wife could have died.”

Also, a volunteer (almost like the 2IC) with the PHC who does not want his name to be mentioned here, says they have been crying for help for years.

“This is the only PHC in Kwamarawa. If something happens at night to a pregnant woman, a sick child, or an elderly man, we can’t do anything.”

“I Feel Helpless When I Can’t Help”

A few kilometers away in Rimayen Rake , the health post is no better.

When I visited Rimayen Rake PHC, the only staff present was the facility’s incharge, Abubakar Ahmad Idris. He stood beside the single damaged bed, carrying a sad face pointing at the only single broken bed in the clinic.

“This is the only bed we have, and it’s broken,” he said, eyes downcast. “We don’t have the tools to do our job. When someone in labor comes, I feel helpless. There’s nothing we can do.”

According to Maimuma Mansir, the clinic is no different from the normal chemist.

“I only go there if my child is sick to buy normal drugs or collect injections. We pay for the drugs except for the regular immunization. That one is free.”

Aisha Namoda, a mother of two, shared her experience.

“My son had a severe fever. He was burning up. We came here, but they said there were no drugs. No nurse. They told me to find transport to Bichi town. We almost lost him.”

No Salaries, No Equipment, Just Volunteers Trying to Help

At Bum Bum PHC, we met Aminu Isiyaku, the second incharge. He isn’t even a government employee. He said he has been volunteering for over 10 years.

“I’m just a volunteer,” he said. “I help the incharge, the only permanent staff here. We have no equipment, no beds, no delivery kits. The only thing we can do here is immunization.”

A visibly pregnant woman, Nana Usmanu, sat nearby, waiting with a look of resignation.

“This is the closest PHC to me. But when it’s time to deliver, I’ll have to find transport to Kano. I don’t trust this place with my life.”

A Once Renovated PHC Now Falling Apart Again

Tsaure PHC once had hope. A private benefactor helped renovate the building. But today, the ceilings hang loose, windows are shattered, mattresses are exposed foam with no covers. There are three beds, but no medical staff use them.

“We try,” said one volunteer. “But there’s no electricity. No water. And we are not trained to deliver babies.”

Hauwa Ado, a 24-year-old mother of four, stood outside holding her baby.

“When I gave birth to this child, I went all the way to Murtala Specialist Hospital in Kano city. I couldn’t risk coming here. This place is only for vaccines.”

In the Heart of Kano, the Same Neglect Even in the city

In Kano Municipal LGA, the Emir Palace PHC mirrors the same neglect. The facility incharge, Maryam Inuwa, sighed as she spoke.

“The government is not helping. We rely only on support from the Basic Health Care Provision Fund. We do our best, but it’s not enough.”

Parents like Musa Yakubu, who brought his feverish toddler for treatment, were told to go elsewhere.

“They checked his temperature and gave us a prescription. That was all. No medicine. No tests. I took him to a private chemist later,” he said.

What a PHC Should Be and What These Are Not

According to the National Primary Health Care Development Agency, a standard PHC should have:

- Trained doctors or nurses

- A labor room with clean beds

- Functional toilets and water

- Constant electricity or solar

- Drugs and diagnostic tools

However, based on our findings, none of these five PHCs meet even the most basic of these requirements.

Budgets on Paper, Not in Practice

Over the past four years, Kano State has allocated approximately N14.7 billion for capital expenditures aimed at enhancing primary healthcare services. However, official budget performance reports reveal that none of these funds were disbursed during this period, leaving PHCs without the promised upgrades, equipment, or staffing improvements.

In 2024 alone, Kano State budgeted N5.1 billion for PHC capital projects, yet by the end of the first quarter, not a single naira had been released (Solacebase, 2024). Similarly, previous years saw N4.1 billion allocated in 2023, N3.4 billion in 2022, and N2.1 billion in 2021—with zero actual expenditure recorded.

Additionally, The Investigator reported that in the same 2024 budget, N3.3 billion was set aside for constructing new health centers, while N17.8 billion was allocated for rehabilitating existing ones. But no funds were released for new constructions, and only 7.8 percent—about N1.39 billion—was disbursed for rehabilitation.

This disconnect between budget allocations and actual spending has left many PHCs in a state of disrepair, lacking essential infrastructure, medical supplies, and adequate staffing.

As one health worker noted, “Funds may be allocated, but they don’t reach us. We don’t see them. We only hear about them in the news.”

A System on Its Knees

From Bum Bum, where Aminu Isiyaku has volunteered for over 10 years with no salary, to Tsaure PHC, which now rots after a renovation, to Emir Palace PHC in the heart of Kano city, the message is the same:

“We try our best,” says Maryam Inuwa at Emir Palace, “but we can’t do much with empty hands.”

The Real Impact: Lost Lives, Broken Trust

Every community shared stories of pregnant women taking dangerous journeys at night. Of children dying from preventable diseases. Of people with disabilities left without care.

At Kwamarawa, one elderly resident, Karimatu Danlami, put it plainly: “It’s not a clinic. It’s just a building with a signboard.”

System Abandoning Its People

These PHCs were meant to bring healthcare closer to the people. Instead, they have become symbols of state failure. Understaffed, under-equipped, and unaccountable.

Residents no longer expect anything from them. Volunteers do their best, but without tools or training, they can only do so much.

As Abubakar Idris of Rimayen Rake said, standing in the ruins of his PHC:

“We’re not asking for a hospital. Just a place where a woman can safely give birth, children and people living with disability can have good healthcare access”

Indeed, the failure of primary healthcare ripples upward. Kano General hospitals like Murtala Mohammed are now overcrowded hubs of desperation.

“Until these gaps are bridged, Kano’s rural and urban poor will remain on their own, in pain, in danger, and unheard.” Anonymous senior health worker noted .

This story was produced for the Frontline Investigative Program and supported by the African Data Hub and Orodata Science.