By Yahuza Bawage

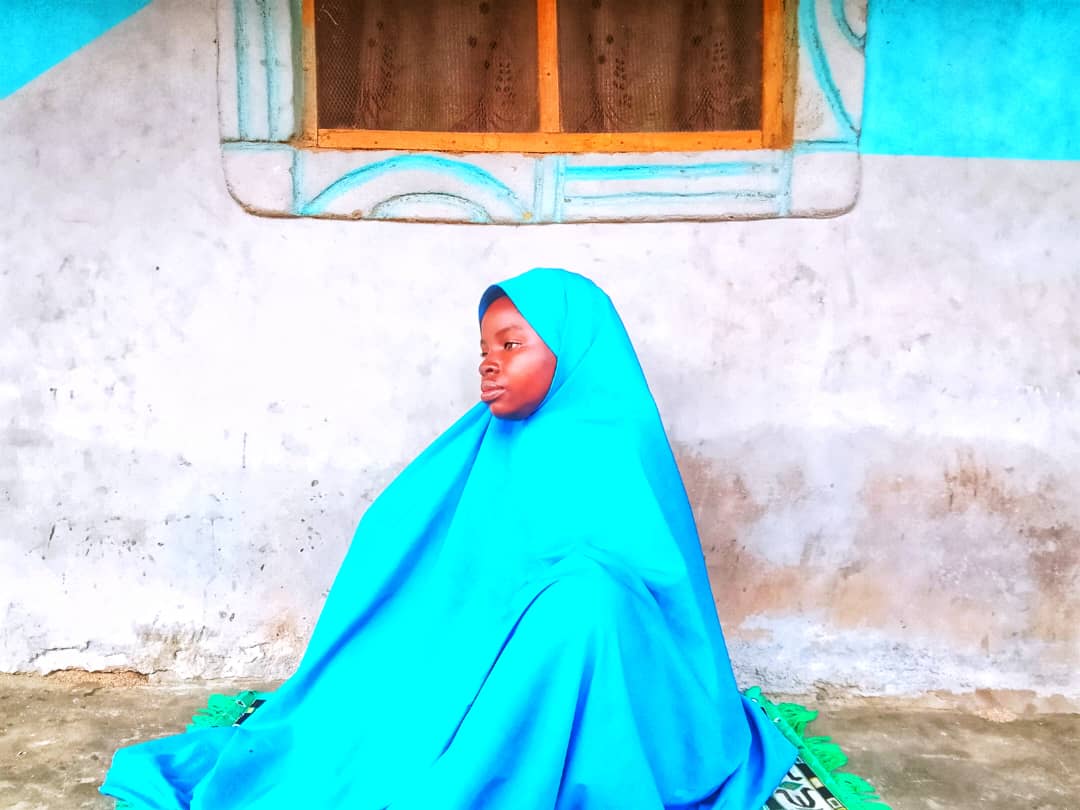

Years have passed since Zainab Usman last visited the Mafindi Primary Healthcare Centre (PHC) in Jalingo, the Taraba State capital. She cited unprofessional staff as the reason, recalling a time during her pregnancy when a disturbing fever made her fear her baby wasn’t moving.

This prompted her to visit the PHC, located only a stone’s throw from her home. Following brief checkups, she was told the fever was stopping the baby’s movement.

“They told me not to worry after giving me several injections,” Zainab recounted. Days after her discharge, her condition worsened. She then sought care at Khairat Clinic and Maternity, a private hospital in Jalingo. It was there a doctor confirmed the baby had died in her womb, necessitating a caesarean section. The ordeal left Zainab questioning the standard of care at the Mafindi PHC.

Even with few professionals at the PHC, Zainab claimed that inexperienced staff were often left to attend to patients.

Not only that, Zainab often found essential medications unavailable at the PHC. “They would tell you there are no drugs, leaving you to buy them outside at private pharmacy shops,” she explained.

Zainab’s painful experience reflects the widespread challenges faced by countless Mafindi residents who depend on the PHC for their basic healthcare needs.

Halima Musa, a mother of six, also noted the persistent shortage of essential medications and health workers’ failure to attend to patients promptly.

“When we take patients to the facility, the workers usually write down the medications and ask us to go to private pharmacy shops to buy,” Halima stated. “Not only are these shops often far from my home, leading to additional expenses, but they also cause significant delays in treatment.”

She added that her experience taking her children to the Mafindi PHC for treatment over the years had been consistently poor. As a result, she now found it preferable to take patients to a private hospital near Jalingo main market, despite it being 1.2 kilometers away, as the Mafindi PHC lacked even basic medications like those for typhoid.

Investigations into the Mafindi PHC revealed that the facility contains just three wards, each accommodating a maximum of four patients, which indicates its inability to support more than 15 patients simultaneously.

Despite this capacity, only three patients were found receiving treatment during this reporter’s visit.

Adding to these observations, the number of workers present at the time did not exceed three. Such limited staffing means the facility could struggle to manage emergency cases promptly.

There is also a non-functional ambulance parked near the entrance of the administrative block.

The issues at Mafindi are mirrored at the Old Barade Modern PHC, where staff shortages are common, often leaving patients without immediate care and compelling them to seek alternatives at private hospitals.

Like many others, 42-year-old Abubakar Jibril frequently endures hours of waiting for staff to source medications elsewhere. When parents take their children to the PHC, he said, they expect timely and seamless service, but this is rarely the case.

“The situation forces us into private clinics, which comes with a huge financial burden,” Abubakar lamented. “Sometimes, we simply cannot afford it.”

A health worker at the Mafindi PHC, who chose not to disclose his name, explained that medication supplies reach the facility through two channels. One source is periodic government provisions through the Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF) programme, while the second is procured and stored by the PHC management in the facility’s pharmacy.

“Even with these two ways, we sometimes have to go out and buy certain medications like anti-malaria drugs, because they are costly and simply aren’t supplied frequently to us,” the worker admitted.

Despite these procurement methods, essential injections and other medications consistently remain unavailable at the facility.

Similarly, patients visiting Hon Imam PHC in Jalingo are sometimes forced to purchase medications or medical equipment from outside the facility.

Under its mandate, the National Primary Healthcare Development Agency (NPHCDA) sets minimum benchmarks for essential drugs and consumables across PHCs. These directives are designed to ensure that every PHC is equipped with a core collection of medicines and supplies. The established framework includes a prescribed list of essential drugs and a robust method for evaluating their accessibility and maintaining sufficient quantities.

A key component of these standards emphasises the necessity of having enough medication in stock to cover at least four weeks of consumption, based on each facility’s typical usage patterns.

The health worker at Mafindi PHC specifically demanded the renovation of the pharmacy and a broader upgrade and equipping of the facility’s laboratory. He explained that these improvements would directly address medication shortages and also mitigate patient frustration.

Abubakar, on behalf of patients, called on authorities to thoroughly investigate the lack of essential medications across PHCs in Jalingo and to propose effective, long-term solutions

“We need medications to be always available at the Mafindi PHC since it’s the one that’s closer to us,” Halima remarked.

Zainab, reflecting on her own ordeal, stressed the importance of Mafindi PHC’s management ensuring that trained professionals are consistently available to attend to patients.

This story was produced for the Frontline Investigative Program and was supported by the Africa Data Hub and Orodata Science.