The uncomfortable logic of privilege on fairness, fear, and oppression across dividing lines

By Adetimilehin Inioluwa Victor (Vic’Adex)

“No matter the mask that oppression wears, we know it.” – Vic’Adex

A few years ago, I caught myself in the middle of a protest. The feminist protest. A protest of women demanding equal rights as men. I had no challenge agreeing with the concepts I first learned. I was raised by a strong woman, one who set the bar high. So high that over two decades of her nursing and nurturing have left me with what my friends jokingly diagnose as “a high taste in women.”

She was the first in her family to become a graduate. That feat did not come cheap. A nurse, a property owner, and a business manager, my mother made more out of less than many who had more ever did. In fact, I doubt if the result could have been better, even if the conditions were. I suppose the little boy in me began to look for pieces of her resilience in every woman he met.

This article will draw some uncomfortable lines. It will trace the contours of three different disadvantages to help surface the fears many carry. And, hopefully, help us start a more honest conversation with ourselves.

When you strip disadvantage of all its language, at the core of it is a power dynamic. A quiet struggle. An open secret. I believe in equity, not mere equality. Still, there was a time when the sheer volume of women empowerment programs in the country began to unsettle me.

I would skip job listings with the tagline: “Women are strongly encouraged to apply.” And when I did apply, I wasn’t optimistic. I assumed the organization was looking to fulfill a gender quota. Given the talent pool, it would be impossible not to find a capable woman to take the role. The odds weren’t in my favor. I know I’m not alone in this feeling. Some can say it out loud. Others cannot. Especially in a society like ours, where anti-trending thoughts are sacred cows. Say the wrong thing and you risk being mauled by Feminist Twitter NG.

But then I remembered my roots. My love for Pan-Africanism. My admiration for reparations and minority quotas in the US. And I began to realize the hypocrisy of my discomfort.

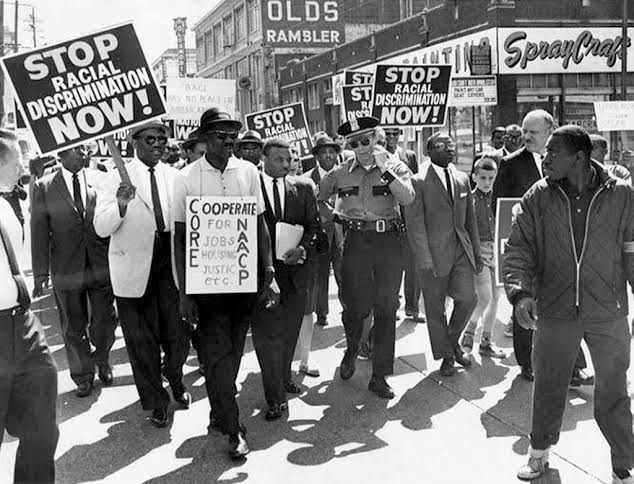

How could I understand that centuries of denial in America—denial of land ownership, voting rights, and education—have left the average Black family disadvantaged, yet fail to see the same logic at play for the Nigerian woman?

Perhaps in her lineage, no woman ever owned property beyond a petty store. Perhaps none ever earned more than a market income. How could I then claim that this history had no impact on the way we now approach women’s rights and roles?

At that moment, I felt like the poor white farmer in those old MLK and Malcolm X speeches. The one who starts protesting the success of a Black sharecropper. Why? Because with hard work, that Black man begins to outperform him, threatening his perceived dominance in that small sphere of life. On what grounds does the farmer feel entitled to the market share? And on what grounds did I feel entitled to jobs I hadn’t even secured?

There’s another way to understand it

It’s the same sense of betrayal that indigent students feel when scholarships meant for the underprivileged go to wealthy children—kids whose parents can easily afford the fees. The resentment isn’t necessarily hatred. It’s the pain of being overlooked in a system that claims to be correcting past wrongs.

And so I ask myself: How would this one empowerment program I missed out on truly affect the value of my life, especially when I’ve done so little with the ones I’ve previously received?

Privilege, whether male or white, is not the absence of difficulty. It doesn’t mean life is easy. It simply means you are spared certain types of scrutiny. No one assumes you slept your way to the top. You’re not expected to prove yourself twice as hard just to be accepted. You don’t get mocked simply for the makeup of your chromosomes. And yes, there are times in your life when you were quietly relieved not to be a woman.

That’s privilege.

How is denying a house to a single woman in Lagos any different from denying Black families in Jim Crow America the right to live in white neighborhoods?

A Few More Notes

Tribalism

As a student of Pan-Africanism, I’ve devoured literature condemning the mistreatment of colored people. I often recite Dr. King’s words like a mantra: “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

But then I see people who support #BlackLivesMatter proudly swear never to allow their child marry from a different tribe. How does that make sense?

Even within the Yoruba ethnic group, I’ve faced this. Some recoil when I mention my sub-ethnic background. Apparently, it has a reputation. For selfishness. For fetish practices. The revelation of my paternal origins has ended what could have been beautiful relationships. It’s painful. Not because of lost love, but because of what it says about us.

Internet Scam

I’ve heard people justify fraud, calling it a way of reclaiming wealth stolen from Africa. If that logic holds, then wouldn’t a woman scamming a man as revenge for past emotional betrayal also be valid?

The logic, when abused, becomes a poison we sip willingly. Until it eats through the very justice we claim to defend.

The Parasitic Quest for Superiority

In Lagos, I met a poor man who still believed he was superior to others. Simply because he was a Lagosian. He had exposure, proximity, access. He considered himself better than people in sub-urban towns.

That’s the lie: that your poverty is still a kind of privilege. That you’re better off, even if you’re worse off.

And from that lie springs discrimination. Not always from power, but from desperation. From the need to matter, even if falsely.

We wear oppression in many garments. Sometimes as victims. Sometimes as perpetrators. Sometimes as both.

But oppression, no matter the mask it wears, leaves its footprints. And when we stop making excuses, we learn to trace them. Not just in others, but in ourselves.

This essay is part of a wider body of reflections on learning, communication, creativity, and culture.

Adetimilehin Inioluwa Victor (Vic’Adex) is a serial creative: poet, essayist, strategist, and cultural curator exploring how communication, culture, and creativity shape social impact.