By Sani Khamees

Nigeria, often recognised as the ‘Giant of Africa’, is rich in natural resources and fertile land, and it boasts a large population and considerable human capital. Despite these assets, the country faces numerous challenges in becoming a strong, stable nation, mainly due to ongoing instability and institutional failure that weaken the state. Since gaining independence from Britain on 1 October 1960, Nigeria has struggled to establish effective governance and political stability. Due to persistent political issues, Nigeria is quickly nearing a state of failure.

To understand Nigeria’s predicaments, it is imperative to offer crucial insights into contemporary challenges and to outline pathways for state reconstruction. The legacies of colonialism, corruption and economic mismanagement, militant groups, armed banditry and insurgencies, and unemployment have continued to predetermine the future of Nigeria as a country.

Nigeria was formed as a political entity in 1914 by the British colonial authority, merging the Northern and Southern Provinces for easier governance. Before this, the area called Nigeria was home to great empires and vibrant kingdoms, each with its own political and socio-economic systems. These included city-states like the Sokoto Caliphate, Kanem-Borno Empire, Ife, Benin, and Oyo, as well as Niger-Delta city-states and civilizations such as Aro, Igbo Ukwu, and Nok. Many analysts attribute post-independence problems to these issues, but as a Pan-Africanist, I believe colonialism is the root cause of Nigeria’s governance crisis. The British colonial government, upon exerting control, delegated authority to leaders who submitted to them and replaced dissenters. Warrant chiefs were appointed in areas lacking suitable organizational structures. The colonial system was inherently corrupt, built on exploiting and plundering of metropolitan resources. Over time, appointed chiefs became complicit in exploiting the people and land through illegal means, showing no regard for human welfare.

After gaining independence, the first republic (1960-1966) inherited a flawed system with structural issues, which quickly led to regional conflicts and crises. Military interventions, starting with the failed coup in January 1966, worsened the situation by disrupting the fragile political order and suspending the constitution. The colonial policy of ‘divide and rule’ became apparent in the military, fueling ethnic competition for power after the assassination of key politicians from the North and West. General Aguyi Ironsi, who took power following the January 1966 coup attempt, established a unitary government, centralising authority in the capital. This marginalised other tribes, as he was an Igbo. In response, the northern officers launched a counter-coup, installing General Yakubu Gowon as head of state. Previously, General Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu had been appointed by Ironsi as military administrator of the Eastern Province, and he declared secession, creating the independent state of Biafra. This led General Gowon’s government to declare war on Biafra, further tearing apart the unity among Nigeria’s tribes.

The discovery and exploration of oil benefited Nigeria’s economy in certain aspects but also caused excessive reliance on crude oil revenue. The Murtala/Obasanjo government launched ambitious development initiatives that did not succeed due to ineffective implementation. Later administrations—Shagari, General Ibrahim Babangida, and General Sani Abacha—and the return to democracy in 1999, entrenched corruption and widespread human rights violations.

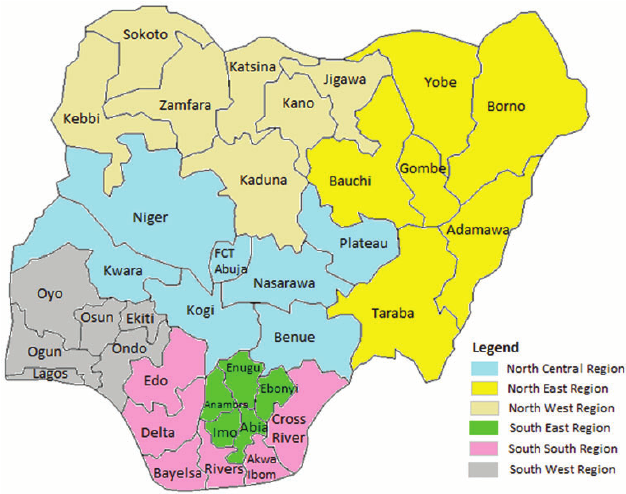

Nigeria continues to face insurgencies like Boko Haram, ISIS, Lakurawa, the Niger Delta militancy, and armed banditry. These conflicts have destabilised the political system and impacted public happiness, resulting in many deaths and loss of livelihoods, with the government showing little concern. All levels of government have failed to address these issues due to weakness and fragility. Nigerian international borders serve as routes for insurgents to trade weapons and stolen cattle, while the airspace is also vulnerable. There are reports of helicopters supplying weapons to Boko Haram and bandits in northern Nigeria. Foreigners have been seen in gold-rich areas, considered no-go zones for citizens, fueling suspicions about government involvement and the actions of some political leaders and international actors. The political class has made security agencies personal defensive, mainly responding only when attacked. On many occasions, I have been stopped by military personnel on the Funtua-Gusau road, under the pretext that bandits are crossing.

This results from widespread corruption within the state and its agencies. Some security personnel have transformed the insurgency into a lucrative business. In fact, many have colluded with insurgents in heinous acts, and several stakeholders, including Sambo Dasuki, the ex-national security adviser, have been caught diverting funds meant for buying weapons to fight Boko Haram.

Nigeria is fast approaching a failed state because it exhibits all the typical signs. Its institutions, including the judiciary, electoral commissions, police, armed forces, and paramilitary groups, are weak, inefficient, and lack independence. The political elite controls these institutions by appointing leaders and managing their salaries, ensuring accountability only to themselves. In some parts of the Northwest, insurgents and gangs have taken over authority, compelling residents to pay taxes before farming. Nigeria suffers from poor governance, corruption, restricted political freedoms, human rights violations, high poverty and unemployment rates, hunger, external debt, and collapsing social services like health, education, transportation, electricity, and water which clear indicators of a failed state.

However, unlike some states that have experienced complete government collapse, Nigeria has faced a gradual decline of its institutions over many decades. Currently, nothing in the country is functioning correctly. Thus, implementing simple institutional reforms has become highly challenging.

Moving forward, Nigerian state reconstruction must incorporate genuine constitutional reforms to curb the executive’s excessive influence over vital institutions such as the judiciary, electoral bodies, and security forces. Broad-based political education should be promoted across all societal levels to renegotiate the social contract between citizens and the state. Pan-African institutions ought to inform African nations about imperialism and the ongoing re-colonisation by Western powers to avoid the mistake in Libya. The collapse of Libya’s state significantly facilitated the spread of small arms in West Africa, fueling insurgencies. African countries must assume control over their development and resources. The pursuit of Nigerian mineral wealth, such as gold, has sparked armed banditry in the northwest, Boko Haram’s insurgency in the northeast, and secessionist efforts in the east. Nigeria’s future stability hinges on transforming its political structures rather than just managing them. Since most state officials are corrupt, reforms must start at the grassroots, with ordinary people and youth reclaiming their future.

Sani Khamees is a community activist, a Pan-Africanist and an independent researcher.

Facebook: SaniKhamees@facebook.com

Twitter (X): @Khamees _sa54571